50.Sholay

The 'Sholay' unit had a ten - to fifteen-day schedule in Bangalore every month, from October 1973 to May 1974. Each time they managed to get some work done, but not enough. The delays were further compounded

because 70mm required that each shot had to be taken twice. After seven months work, hardly one-third of the film had been shot.

'Sholay' had been planned as a six-month project. Nobody imagined that eventually it would take so long that Macmohan, playing Sambha, one of the smallest roles in the film, would travel twenty-seven times from

Mumbai to Bangalore.

Ramesh retained his famous cool. He had a grand vision of 'Sholay' and wasn't going to let delays force him to make compromises. As the budget soared beyond the original one crore, G.P Sippy did make the occasional noise. 'What the hell is going on?' he would ask. But he never pulled the plug.

He was a gambler going for the big one. The funds kept flowing.

Yet, despite all the planning, things started to go wrong. The first schrdule was ten days long, but very little work got done. Some days they managed to get ten shots right, and on others, none at all.

In the November schedule, Ramesh completed only one scene. The No Compromise resolve was set in stone.

Ramesh and Divecha were like painters trying to perfect their canvas, with G.P. Sippy, a patron of the arts,

bankrolling their dreams, budget and timetables took a backseat.

'Sholay's centerpiece - the massacre sequence in which Gabbar obliterates the Thakur's family - was shot in twenty-three days over three schedules. It was a complicated scene with several parts: establishing the family, Gabbar's arrival, the shootings, and then the Thakur's arrival on the scene after Gabbar and his men have slaughtered his family and retreated.

Half the scene had been shot when the weather changed and the bright sun was replaced by an overcast sky.

For two days, the unit waited for the sun to reappear. Then Ramesh realized that the dark clouds were a celestial signal: the overcast look was perfect for the scene. It underlined the tragedy and heightened the sense of doom. It also logically led to the point where the wind starts to build up and dry leaves are blown over the dead bodies. He conferred with Divecha. 'It won't just look good,' Divecha said, 'it will look very good. But what will we do if the sun comes out tomorrow?' Ramesh was willing to take the chance.

'Let's shoot,' he said.

They shot furiously for the next two days. And then the sun popped out again. After a week of work, they had two versions of the same half scene, one against a bright sky and the other against an overcast one.

But Ramesh was determined. It was going to be clouds or nothing. So they waited for the gods to do the lighting. With the sun playing hide and seek, there were days when they managed to get only one shot and some when they simply stared at the skies. Filming came to a complete halt.

To speed up the process, Divecha asked Anwar to make a screen to bounce the light off. The screen had to be bigger than the house.

Anwar ended up buying all the white cloth in the vicinity to create a seventy-foot-by- hundred-foot screen.

He stitched it himself with strong canvas thread.

With the huge screen in place, shooting was resumed, but there were shots for which the effect created by the screen wasn't good enough. The gods had to intervene and bring back the clouds.

But it wasn't just the clouds. Nothing seemed to go right. As they neared the end of the sequence, the little boy playing Thakur's grandson, Master Alankar, had exams. He would lose an academic year if he didn't sit

for them. Ramesh let him go. Then the propeller, which worked up an appropriate wind to blow dry leaves onto the dead bodies, decided to do its own thing. It wouldn't start when they needed it to. And once started,

it would just keep going. Finally, an aeronautics unit near Bangalore built another propeller. It worked perfectly. The wind blew yellow-brown leaves onto the bodies and the white shroud off them, Thakur mounted his horse in a raging fury, ready to look for Gabbar.

Almost as time-consuming were the sequences of Radha extinguishing the lamps while Jai played his harmonica and watched. These sequences establish the gradual, wordless bonding between the widow and the thief - the sympathy and admiration slowly turning into love.

Capturing the right mood was critical. These were two sequences, only about a minute each in the final film, and it took twenty days to shoot them.

Ramesh and Divecha decided to do the scenes in 'magic hour', a cinema term for the time between sunset and night. The light that falls during magic hour is dreamlike in its warm golden hue.

The director and cinemtograher wanted specifically the velvety dusk which arrives at the tail end of the golden hue. A shadowy darkness precedes nightfall, but it is still light enough to show the surrounding

sillhouettes. Essentially, they had only a few minutes to capture the shot.

The preparations for the shot would begin after lunch. The lights and the camera set-up would be in place well before time. At around five in the evening they would rehearse the shot and the camera movements.

Then between six and six-thirty as the sun started to set, there was total pandemonium. Everyone ran around

shouting, trying to get the shot before darkness. sometimes they would get one shot, sometimes two and very

rarely with great difficulty, a third re-take. But there was never any time to change the set-up.

Ramesh wouldn't settle for anything less than perfection. Invariably there was always some mess-up.

The sun set earlier than expected, a lightman made a mistake, the trolly movement wasn't right, some object was lying where it shouldn't have been. There were times when Jaya lost her cool: 'Ramesh, no one can see me,' she would say. 'It's a long shot, no viewer on the planet is going to be able to see the mistakes in continuity.' The answer always was: 'No, no, one more take.' Ramesh dressed each frame.

The Lady-of-the-lamps shot became a kind of a joke. It took several schedules to get it right.

In fact, in terms of time taken, each sequence seemed to compete with the next.

Ahmed, the blind Imam's son (played by Sachin), for instance, took seventeen days to die.

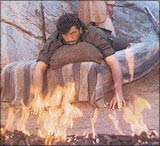

It was a long and complicated sequence, and originally it also included the actual act of killing: meat is roasting in the foreground; Gabbar points a red-hot skewer at the boy and with a gleeful look tells his gang,

'Isko to bahut tadpa tadpa ke maroonga.' But this never made it to the final cut. Instead, the scene cuts from

Gabbar killing an ant to Ahmed's horse carrying his dead body into the village.